By the time most kids turn one, they should be using simple gestures (waving “bye bye”), saying a few words (“mama” or “dada”), playing basic games (“peek-a-boo”), following simple directions (“bring me the toy”), and cruising or standing alone. Of course, this is just a handful of examples from a large list of standard milestones. When it comes to typical infant and child development, “normal” can mean many things.

As if we didn’t have enough to worry about between making sure that our offspring eat enough and sleep well, there’s also an exhaustive list of standards that children have to meet. Long before we send them to school, they already have to pass tests, and some kids weren’t born with the right tools to pass them.

It’s common advice these days to shrug off that set of standards. You hear it all the time from well-meaning parents, strangers in the checkout line, and even friends. “Oh, he’s not talking yet? Suzie Q. didn’t talk until she was three, and then she never stopped!” They wave away your concerns and tell you that your kiddo will be just fine.

But what happens when he’s not just fine?

As I sat in the doctor’s office for Arthur’s 12-month checkup, running through my list of questions, I hesitantly brought up some of our biggest concerns.

“He doesn’t smile much, and he hates other kids. I think he’s afraid of them,” I said, knowing that these would be red flags because, as usual, I had already googled this subject enough to earn my degree in internet medicine. “He also doesn’t clap. And he hates grass, like really hates grass.”

After alleviating some of my concerns, Arthur’s doctor suggested a referral to Early Intervention. I agreed to the referral, but I also had that same sinking feeling you get when your boss pulls you into the conference room to talk about your work performance.

No mom likes to hear that there’s something abnormal about her child.

Arthur had always tracked well in physical growth, and his gross motor skills were great. But by 12 months, he hadn’t said a word (not even “mama” or “dada”), he wasn’t very social, and he had issues with textures. He also seemed to lack the fine motor control of even younger kids. We had a lengthy mental list of things he didn’t do. And while there’s a range of “normal” in infant development, these parameters exist for a reason.

Standards are standards, even with the wide margin that exists for the under-three crowd.

Fortunately, there’s an app for that.

Okay, it’s not an app. It’s a state government-run program designed to help infants and toddlers catch up if they’re behind. In Tennessee, it’s called Tennessee Early Intervention System (TEIS), but it goes by other names in other states. TEIS is a part of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Straight from the TEIS website, the program’s stated purpose is to:

Support families in promoting their child’s optimal development;

Facilitate the child’s participation in family and community activities; and

Encourage the active participation of families in the intervention by imbedding [sic] strategies into family routines.

When the TEIS evaluator came to our home for the initial visit, I didn’t know what to expect. I woefully underestimated the extent of the questions she asked. Starting from the time Arthur woke up until bed, she went over minute details of his day, including when he woke up, when and how and how often he ate, the specifics of our playtime activities, and what he could and couldn’t do so far. After the interview, she said that she would score my answers against Tennessee’s development guidelines to see if Arthur qualified for services.

He did, in fact, qualify for services.

A child has to be slightly delayed (25 percent) in two areas or significantly delayed (40 percent) in one to qualify for services. TEIS evaluates five areas: motor, communication, cognitive, social, and adaptive. If your child qualifies based on any of these areas, then she can still get help in any of the other areas. Arthur scored just below the cutoff in two areas, but we work on other areas as well.

After the evaluator determined that Arthur qualified, we met with a service coordinator. Her job is to develop a plan with the family’s input for addressing development delays. Because TEIS stops at age three, the goal is to provide as many services and as much support as possible for kids until they get to preschool. At that point, different programs exist for addressing special needs.

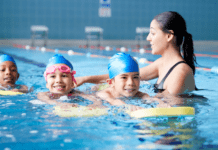

Each week, a developmental therapist comes to our home and spends an hour with me and Arthur. She writes down progress notes, suggests areas to work on, offers ideas for addressing specific things, asks about my concerns, and fills out a worksheet with goals for the following week.

Every other week, we meet with an occupational therapist. When we started, it was weekly. Arthur tested substantially behind in fine motor skills (testing at an 8-month level when he was a year old). He doesn’t have an officially diagnosed sensory problem, but he does show signs of sensitivity in certain areas. Arthur’s sensory problems are a whole ‘nother story, but even in this area, he’s improving. He doesn’t even hate grass anymore, though he is a little wary about sitting in it for too long.

Early Intervention helps families help their children.

It also helps families pay for needed therapy services that might otherwise cost too much. Our service coordinator called TEIS a “payer of last resort.” In our case, that means they bill our insurance and cover the rest of the cost. We haven’t had to pay anything out of pocket for Arthur’s therapy over the last eight months.

Arthur now tests right on target for his age in fine motor development, a vast improvement over where he started. He smiles, waves, claps, and says 66 words (not that I’m counting). He may have done all of these things on his own eventually, but without TEIS, it may have taken much longer.

Research consistently shows that early intervention services can improve long-term educational and behavioral outcomes in children. It’s also less costly to address problems upfront than to try and remedy serious delays later in life.